Peter Usanga

Debris from a Chinese rocket is expected to fall back to Earth in an uncontrolled re-entry this weekend. The rocket was launched to carry a Chinese space station section into orbit.

The main segment from the Long March-5b vehicle was used to launch the first module of China’s new space station last month.

At 18 tones it is one of the largest items in decades to have an undirected dive into the atmosphere.

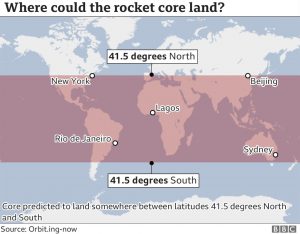

The zone of potential fall in this case is restricted still further by the trajectory of the rocket stage. It is moving on an inclination to the equator of about 41.5 degrees. This means it is possible already to exclude that any debris could fall further north than approximately 41.5 degrees North latitude and further south than 41.5 degrees South latitude, which covers New York in America, Beijing in China, Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, Sydney in Australia and Lagos in Nigeria.

Originally injected into an elliptical orbit approximately 160km by 375km above Earth’s surface on 29 April, the Long March-5b core stage has been losing height ever since.

Just how quickly the core’s orbit will continue to decay will depend on the density of air it encounters at altitude and the amount of drag this produce. These details are poorly known.

Most of the vehicle should burn up when it makes its final plunge through the atmosphere, although there is always the possibility that metals with high melting points, and other resistant materials, could survive to the surface.

The US however on Thursday said it was watching the path of the object but currently had no plans to shoot it down.

“We’re hopeful that it will land in a place where it won’t harm anyone,” US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin said. “Hopefully in the ocean, or someplace like that.”

Various space debris modelling experts are pointing to late Saturday or early Sunday (GMT) as the likely moment of re-entry. However, such projections are always highly uncertain.

When a similar core stage returned to Earth a year ago, piping assumed to be from the rocket was identified on the ground in Ivory Coast, Africa.

The chances of anyone being hit by a piece of space junk are exceedingly small, not least because so much of the Earth’s surface is covered by ocean, and because that part which is land includes huge areas that are uninhabited.