By Chuks Ibegbu

Ohanaeze Chieftain

At the inception of Nigeria, the country existed as two broad entities, the Northern and Southern Protectorates. These later evolved into three regions, Northern, Eastern and Western Regions, forming the early political and administrative foundation of the Nigerian state.

In 1963, the Mid Western Region was created through the political efforts of the NCNC led Eastern Region, a clear demonstration of inclusiveness and accommodation of minority aspirations. However, on the eve of the Nigerian Civil War, General Yakubu Gowon restructured the country into 12 states, effectively detaching minority neighbours from the Eastern Region with the creation of Rivers State and the South Eastern State. The Igbo heartland was confined to a single entity, the East Central State.

In 1976, the East Central State was split into Imo and Anambra States within a 19 state federal structure. Further exercises followed. In 1991, Abia and Enugu States were carved out of old Imo and Anambra States. In 1996, Ebonyi State emerged from parts of Enugu and Abia States. That is where the South East stands today, with only five states.

In contrast, the old Northern Region today accounts for 19 states and the Federal Capital Territory, with well over 400 local government areas out of Nigeria’s 774. The old Western Region has six states, the old Mid Western Region has two, while the old Eastern Region has nine states, of which the South East controls just five. Over time, the Igbo have been structurally reduced to a minority among the so called majorities.

Successive attempts have been made to correct this imbalance. At various national conferences, the South East presented compelling cases for additional states such as Aba, Adada, Etiti, Orashi, Anim, Orlu and others. During the Obasanjo administration, the region nearly secured a parity state, but the controversy surrounding the third term agenda derailed that opportunity. In retrospect, a more farsighted approach might have prevailed.

Similarly, during the Buhari administration, the promise of a parity state for the South East surfaced again as part of broader political negotiations. As spokesperson of Ohanaeze Ndigbo at the time, I witnessed firsthand the internal disagreements that undermined our collective position. While Chief Nnia Nwodo, then President General of Ohanaeze, favoured Adada State, internal consultations showed stronger support for Aba, followed by Etiti. The absence of consensus ultimately cost the region yet another opportunity.

Today, the issue of state creation has returned to the front burner. The Tinubu administration, in conjunction with the National Assembly, has initiated processes aimed at addressing longstanding structural imbalances, including the widely acknowledged need for a parity state for the South East. While numerous requests have emerged across the region, it is unfortunate that our people paid insufficient attention to the equally critical issue of creating more local government areas, despite the fact that national revenue allocation and political representation are largely determined by states and local government areas.

It is now evident that beyond a parity state, the South East may be entitled to at least one additional state, bringing the total to seven. Even if no other region gains a new state for now, there is broad national agreement that the South East deserves, at minimum, a parity state. The responsibility now lies squarely with us to make a coherent and united case.

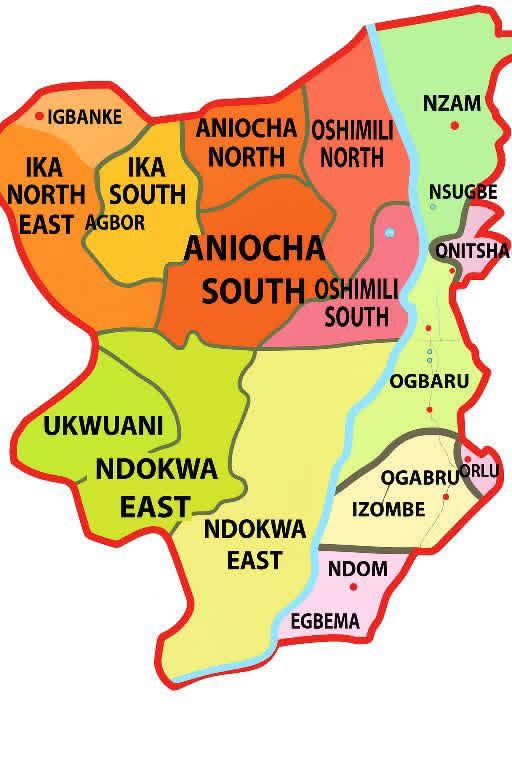

For decades, our kiths and kins west of the Niger have expressed a consistent desire to align politically with the South East. Through their distinguished son, Senator Ned Nwoko, sustained advocacy has been mounted for the creation of Anioma State and its integration into the South East. While a few dissenting voices exist, the overwhelming historical, cultural and economic logic supports this position. Anioma State in the South East would significantly enhance Igbo economic strength, political balance, social cohesion and maritime relevance.

Recent suggestions advocating an Anim Oma State with capital in Orlu, largely driven by frustration over perceived identity disputes, are misguided. Our focus should remain clear and strategic. Anioma State should be our parity state. Thereafter, the South East can pursue additional states such as Adada, Anim, Etiti or Aba, alongside aggressive advocacy for more local government areas. For instance, densely populated local government areas like Bende and Obingwa clearly warrant subdivision into multiple federally funded councils.

The consequences of having the fewest states and local governments in Nigeria are enormous. The South East loses more than four trillion naira annually in revenue allocations and development opportunities due to this structural imbalance.

This moment calls for unity, clarity of purpose and strategic thinking. The ball is now in our court.